Nepal has become the latest country where Generation Z has risen against entrenched political elites, joining a growing trend across South and Southeast Asia.

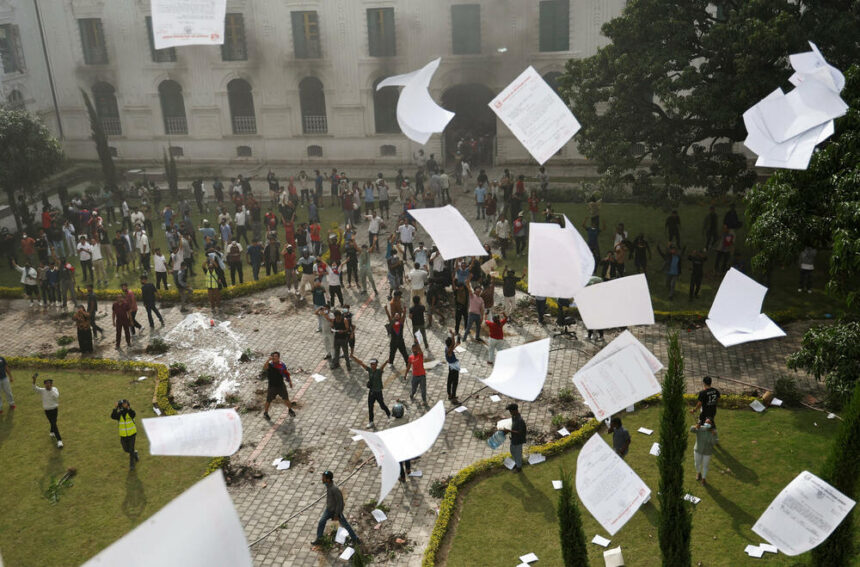

On the streets of Kathmandu, the signs of revolt were unmistakable: bloodstains on sidewalks washed by late monsoon rains, broken household items in looted politicians’ residences, and the smell of smoke from public buildings set on fire. A message scrawled on a marble wall of the burned parliament summed up the moment:

“From now on, only Gen Z will be here. Corrupt leaders will be expelled. Long live Nepal. Long live Generation Z.”

Protests and Resignation

The protests, largely led by people born between 1997 and 2012, erupted after the government blocked access to major social media platforms—but quickly evolved into a broader revolt against a perceived corrupt and aging political class.

After two days of deadly and destructive protests, Prime Minister Kagda Prasad Sharma Oli resigned last Tuesday. Authorities reported 51 deaths and nearly 1,400 injuries across the country.

“We came to revolt against corruption,” said Anjali Shah, a 24-year-old law student. “They could ban us online, but we are on the streets demanding to know how our taxes are spent while they live luxuriously on public salaries.”

Nepal, with a median population age of 25 (below the Asian average of 32), exemplifies the regional clash between older political leaders and a young, ambitious, often unemployed generation frustrated by stagnation and lack of opportunity.

Regional Domino Effect

Nepal is the latest “domino” in a pattern seen across Asia:

- Sri Lanka (2022): Tens of thousands of young demonstrators occupied Colombo’s presidential palace, forcing President Gotabaya Rajapaksa to flee.

- Bangladesh (2024): University students in Dhaka led a massive uprising that pressured Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to seek refuge in India.

- Indonesia (2025): Students protested parliament members’ exorbitant housing allowances, forcing President Prabowo Subianto to revoke the perks and replace the finance minister.

Common factors include aging political elites, corruption, and a young population frustrated by socio-economic stagnation.

“Across the region, Gen Z is signaling that they want change,” says Shafkat Munir, senior fellow at the Bangladesh Institute for Peace and Security Studies. “They have a global perspective, see how others have revolted, and use the internet as a bloodstream for mobilization.”

Social Media as Catalyst

In Nepal, the movement was fueled by viral social media posts exposing the lavish lifestyles of politicians’ children, often tagged #NepoKid or #NepoBabies.

“The movement began by exposing the ‘Nepo Kids’ flaunting luxury while we lack clean water and jobs,” Shah explained.

The protests reflect decades of frustration with political elites who maintain control despite repeated promises of reform. Nepal has had more than ten governments since the 2006 end of the monarchy, with many of the same actors still dominating politics.

Socioeconomic Pressures

High youth unemployment and limited economic opportunities compound political grievances. Over 700,000 Nepalis leave annually in search of better futures, mainly to Gulf countries. Despite remittances fueling economic growth, domestic opportunities remain scarce, fueling further frustration.

In Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia, similar socio-economic dynamics have driven young people to organize politically. Many are forming new political movements, promising reform and accountability.

Looking Forward

In Nepal, Generation Z has already achieved tangible results: former Supreme Court president Sushila Karki now heads the transitional government, parliament has been dissolved, and new general elections are scheduled for March.

“Our age group and dissatisfaction unite us. We protested against corruption and demanded accountability and transparency,” said Jatish Ojha, 25, reflecting on the rapid toppling of Nepal’s political regime in just two days.