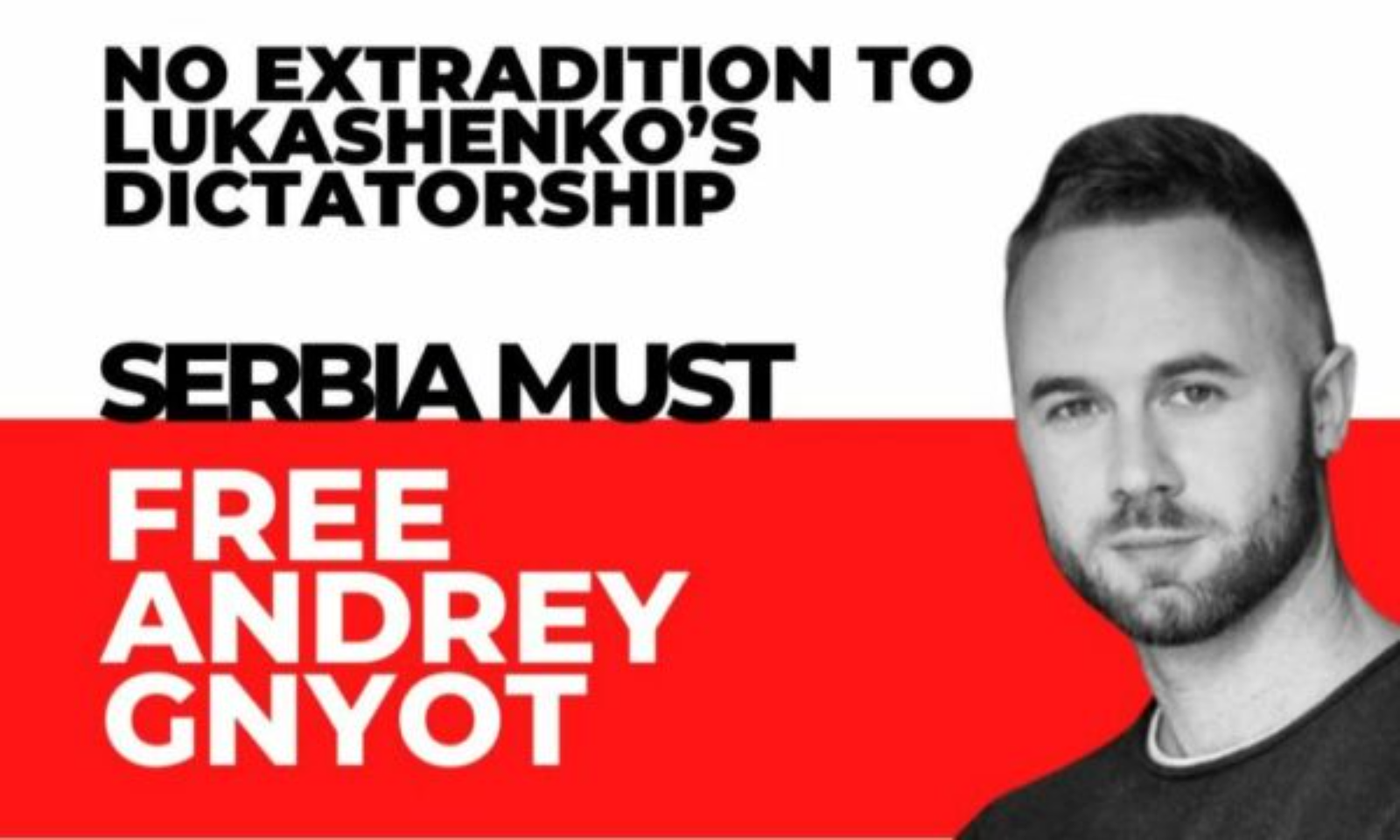

A year after being arrested in Serbia, prominent Belarusian dissident Andrey Gnyot still lives in fear of being extradited to his home country, where he believes he faces torture—or even death.

Gnyot’s difficult situation highlights not only the grim prospects for opponents of Belarus’s strongman, Alexander Lukashenko, a staunch ally of Moscow, but also the delicate balancing act facing Serbia’s leadership between Western rapprochement and historical loyalty to Russia.

“Twenty-five political prisoners have died in Belarus since 2020,” Gnyot told the Financial Times from his house arrest in a Belgrade apartment overlooking a brick wall. “Torture and death await me there, 100 percent.”

Lukashenko has been in power for 30 years and has imprisoned around 1,300 political opponents, according to the human rights group Viasna.

The 42-year-old was arrested at Belgrade airport last year based on an international warrant issued by Minsk for tax evasion charges. He had been living in Thailand since 2021, having fled there after being summoned for questioning by the Belarusian security service, which still bears the Soviet-era name, KGB.

He spoke to the FT immediately after Serbia’s appellate court sent his extradition case back to Belgrade’s highest court for the third time.

European actors and filmmakers, including Juliette Binoche, Agnieszka Holland, and Wim Wenders, sent an open letter to Serbian authorities in August, urging them not to extradite Gnyot.

“It’s a difficult case for Serbia, balancing its image and maintaining good relations with those who support Russia while also pursuing its integration plan with the EU,” said Franak Viačorka, a senior advisor to Belarusian opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya in exile.

“There has been a lot of pressure from Brussels, including from [European Commission President] Ursula von der Leyen, and I think any extradition decision would be a serious blow to relations with Brussels.”

Gnyot stated that he opposed the regime primarily because he helped dissident athletes respond to Lukashenko’s brutal crackdown on pro-democracy protests following his disputed re-election in 2020. The athletes sent an open letter to the International Olympic Committee requesting an investigation into the regime’s harassment and urging the IOC to suspend Minsk.

Gnyot’s association also contributed to Minsk’s removal as a co-host of the 2021 Ice Hockey World Championship, which was ultimately held only in Latvia.

The Belarusian regime claims it wants to punish him for tax evasion, but it previously condemned his work and activism against Lukashenko.

Gnyot recalled feeling safe enough and far enough from Belarus to travel to Serbia a year ago for a film project.

“Instead of filming for clients in Romania and Sweden, I was detained right at the airport,” he remembers.

“I was placed in a room with dozens of people from around the world, cramped with little room to stand, without water, food, or restroom breaks.”

When he told the Belgrade court that tax evasion, “paragraph 243,” had been used by the Belarusian dictatorship to silence its enemies, he recalled the judge responding: “Dictatorship in Belarus? This is the first time I’ve heard of this in my life. Do you have any evidence?”

But Viačorka from the Belarusian opposition said that Gnyot’s arrest should also raise questions about how Interpol can sometimes assist authoritarian regimes.

“Any country can send a red notice to the international database, but it’s a very strange situation when Interpol essentially works on behalf of dictatorships to arrest those whom dictators don’t like,” he said.