Saydnaya prison, perched ominously on a hill just half an hour from the center of Damascus, is notorious for the suffering it has witnessed. Recently repainted with the green, white, and black of Syria’s revolutionary flag, the updated colors do little to mask the sinister atmosphere of this infamous detention center. As I walked through its gates, I couldn’t help but reflect on the despair felt by the thousands of Syrians who had made the same journey.

Reports estimate that more than 30,000 detainees have perished in Saydnaya since the onset of the Syrian war in 2011, contributing to the disappearance of over 100,000 Syrians—predominantly men, but also women and children—who vanished into Bashar al-Assad’s brutal prison system.

While some of Assad’s other prisons were less harsh, offering basic phone calls or family visits, Saydnaya stands as the regime’s dark, rotten core. The fear of being sent there and executed without anyone knowing the fate of the prisoners became a central tool of Assad’s repression. Families were often left in limbo, knowing nothing about their loved ones’ whereabouts, contributing to the regime’s campaign of terror.

The brutality of Saydnaya was unparalleled. I have visited other infamous prisons, including Colonel Gaddafi’s Abu Salim in Libya and Pul-e-Charki near Kabul in Afghanistan. None, however, matched the foul conditions of Saydnaya. The prison’s overcrowded cells forced detainees to urinate into plastic bags as they had limited access to latrines. When prisoners were finally released or the doors were broken open, they left behind filthy rags and scraps of blankets—their only means of covering themselves.

Torture and executions were rampant in Saydnaya, and further revelations about the horrors within its walls will likely continue to surface as more former inmates speak out.

A Record of Atrocities

One of the immediate challenges facing Syrians in the aftermath of Assad’s fall is documenting the scale of the regime’s crimes. Volunteers have begun combing through the disarray of paperwork scattered around Saydnaya’s offices and prison yard, collecting scraps of documentation in hopes of identifying names, dates, or places that will help trace the fate of the disappeared.

The task of preserving these records has become urgent, as international human rights organizations were slow to arrive and evidence continues to disappear. Volunteers like Safana Bakleh, who have taken it upon themselves to document the prison’s history, believe that even the smallest revelation—such as confirming the death of a loved one—can bring a sense of closure to grieving families.

“We are trying to gather whatever evidence we can. Even if one family learns the fate of their loved one, it will give them some peace,” said Bakleh. “It’s chaotic, and we are doing this because international organizations are not here.”

Shocking Realities Inside Saydnaya

The shocking conditions inside Saydnaya left even the most seasoned volunteers in disbelief. Widad Halabi, a volunteer searching for evidence, broke down in tears after seeing the squalid conditions for herself.

“What I’ve seen here is a life not fit for humans. I imagined how they lived, their clothes. How did they breathe? How did they eat? How did they feel? It’s terrible. There are bags of urine on the floor. They couldn’t go to the toilet, so they had to put urine in bags. The smell, there’s no light or sunlight. I can’t believe people were living here,” Halabi said, her voice breaking.

Seeking Justice, Not Revenge

While documenting the crimes is crucial, Syrians also face the challenging task of holding those responsible accountable. Bashar al-Assad and his closest family members have fled Syria, with reports suggesting that his brother, Maher, is in Iraq. Some of Assad’s cousins met their end in a gunfight while attempting to escape the regime’s collapse.

But while the regime has crumbled, finding and prosecuting the individuals responsible for the atrocities remains difficult. At Saydnaya, families continue to search for answers, driven by the hope that justice will one day be served.

“We need justice for the past,” one man told me as he scoured the prison’s grounds for any trace of his missing family members. “We need to know what happened to our loved ones.”

The quest for justice will be long and difficult, but it’s a path that Syrians are determined to follow. For many, this will include not only holding Assad and his inner circle to account but also addressing the widespread corruption that fueled the regime’s control.

Corruption and the Regime’s Legacy

The Assad regime’s corruption permeated every aspect of Syrian life. From telecoms to business deals, the Assad family and their allies enriched themselves while ordinary Syrians struggled under the weight of war and economic devastation.

Prisoners like Hassan Abu Shwarb, who spent 11 years in prison on false charges of terrorism, testify to the depth of corruption within the prison system. His family was forced to pay bribes to officials for his release, only to see the money pocketed without result.

Hassan’s ordeal is one of many examples of how the Assad regime manipulated its citizens, profiting from their suffering. After his release, Hassan, now back home, shared his frustration: “The leaders of this regime should be punished. We are human beings, not stones. The ones who killed should be publicly executed. We cannot move forward until they are brought to justice.”

The Future of Syria

As Syrians begin to rebuild their country, the pursuit of justice is at the forefront of their efforts. But with so much corruption and violence in the past, many fear that the new leaders of Syria may struggle to address the trauma and injustices of the Assad regime.

For Syrians, the future is uncertain, but one thing is clear: The desire for justice and accountability remains as strong as ever.

“The past must be dealt with,” one family member told me. “Only then can we build a better future for Syria.”

The pain is deep, and the road ahead will be difficult. But the fall of Assad’s regime has given Syrians a glimmer of hope. If they can hold those responsible for the atrocities to account, the country may have a chance at healing./ By Jeremy Bowen, BBC

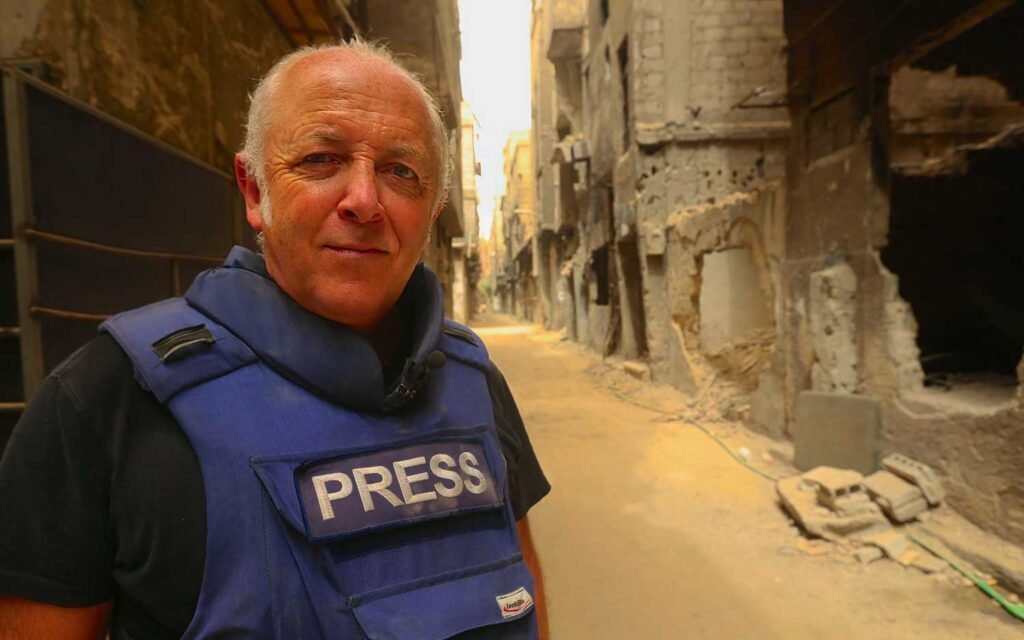

Photo: Jeremy Bowen journalist/BBC news