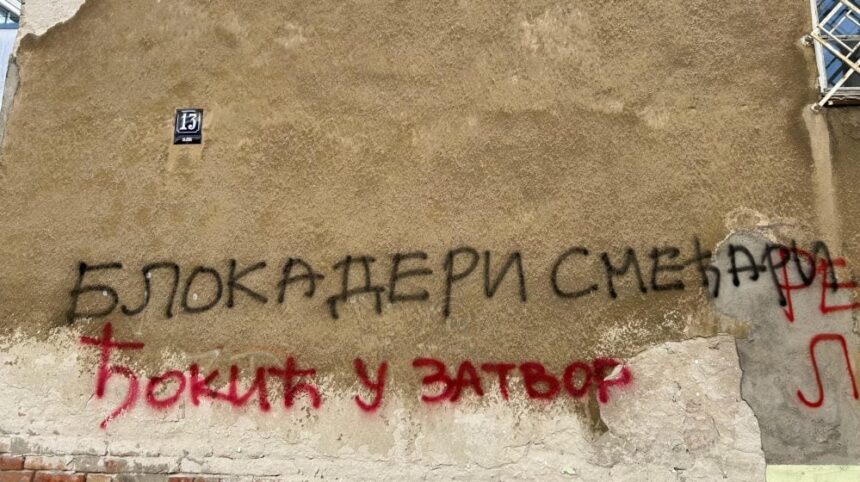

In Belgrade, walls across the city have become battlegrounds for political expression, with graffiti increasingly used as a tool for spreading messages that blur the line between street art and targeted propaganda. While some messages appear as humorous or artistic, many have been identified as hate speech and politically motivated attacks.

Over the past year, repetitive slogans have appeared targeting individuals, groups, and media outlets critical of the government. Examples include “Zoran Kesić – Show must go on,” “Rektor lopov,” “Blokaderi teroristi,” and even attacks on media outlets like N1 and Nova S, with labels such as “NDH1” and “Nova SS,” explicitly framing them as enemies.

Igor Božić, Programming Director of N1, emphasized that these messages are not political criticism but clear hate speech, designed to create a hostile atmosphere and intimidate those with dissenting views. Božić criticized authorities for inaction, stating that attempts to remove these messages were either ignored or required payment, illustrating a lack of institutional protection for targets of hate speech unless aligned with the regime.

Political analyst Nikola Parun noted that such graffiti serve as visual propaganda, influencing citizens—especially older generations—by presenting an illusion of widespread opposition or support, depending on the message. Similarly, Zoran Erić, research associate at the Institute for Philosophy and Social Theory, explained that these political messages reflect societal pathology, aimed at intimidation and delegitimization of dissenters while diverting attention from the criminalized actions of those in power.

Interestingly, counter-messages have also emerged, often humorous or satirical, using street art and banners to resist authoritarian narratives. These acts of visual dissent aim to challenge fear and ridicule the political propaganda imposed on public spaces.

Mitja Velikonja, in his study Political Graffiti, differentiates political graffiti from street art by highlighting that both are illegal visual expressions conveying messages in public spaces. Political graffiti, however, is explicitly a visual political act, blending politics and aesthetics in a way designed to influence public perception.

In essence, Belgrade’s walls are now arenas of political conflict, where messages of dissent confront hate speech, reflecting deeper tensions in Serbian society between authoritarian control and citizen activism.