As the Oil Industry of Serbia (NIS) attempts to survive under U.S. sanctions, the Serbian public is left wondering how deeply this crisis created by years of political dependence on Russia will hit their daily lives and their wallets.

For days, Serbian officials have floated every possible scenario, from the sale of Gazpromneft’s ownership stake, to bankruptcy, to outright nationalization. The growing uncertainty reflects a reality Serbia has long tried to ignore: when you anchor your strategic energy sector to Moscow, the bill eventually arrives.

Serbia’s Minister of Energy, Dubravka Đedović Handanović, announced that Russian owners are now supposedly “ready to give up control and influence over NIS to a third party.” The statement, published on her social media, appears to be a last-minute attempt by Belgrade and Moscow to soften the consequences of sanctions rather than a genuine strategic shift.

According to the minister, Russian shareholders have submitted a formal request to the U.S. Treasury’s OFAC seeking an extension of NIS’s operating license based on negotiations with a third party. She did not disclose who this mysterious party is, but insisted that Serbia “supports the request” and expects an answer next week.

This dramatic tone is striking, considering that for more than a decade, Serbia has insisted that Russia’s dominance in NIS posed no risk. Now, OFAC’s decisions to extend Lukoil’s deadline to divest foreign assets made clear that Washington isn’t interested in symbolic rearrangements. Russia must fully exit ownership.

Serbia, however, is still publicly pretending that this crisis is a surprise.

President Aleksandar Vučić insisted there are “no negotiations with possible buyers,” while Moscow claims it is searching for the “best solution” together with Belgrade leaning again on the outdated 2008 intergovernmental agreement Serbia still treats as untouchable.

Russia’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson, Maria Zakharova, accused the United States of “artificially creating problems” and insisted that Russia and Serbia will “protect their bilateral cooperation from external interference”as if NIS were not a Russian-controlled company operating inside a sovereign state.

Yet the facts are simple:

Serbia chose to place a core energy asset under Russian control. Now the consequences have reached the threshold where neither excuses nor patriotic rhetoric can push them away.

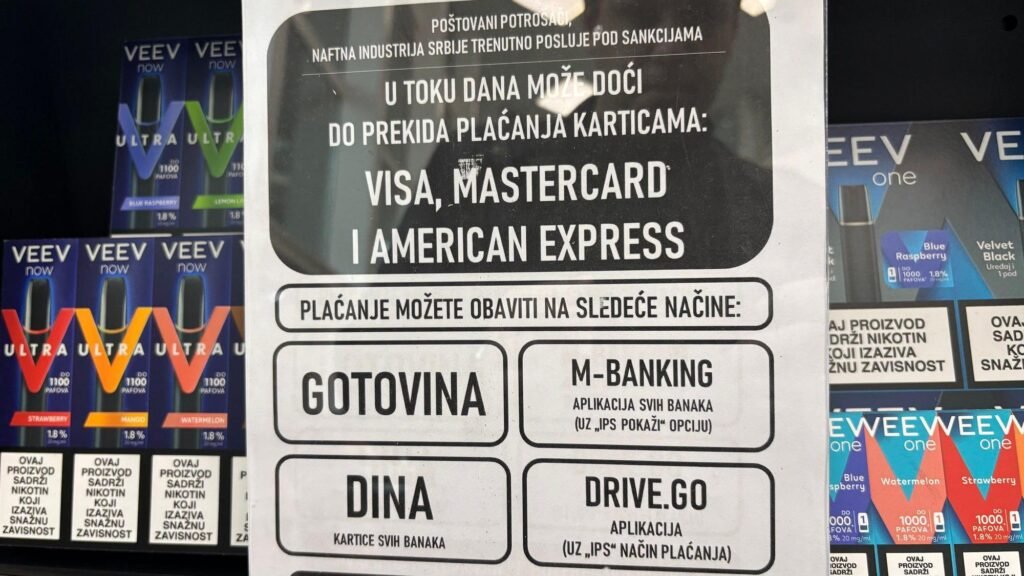

Despite assurances from Serbia’s leadership that “there will be no shortages” and that fuel reserves are sufficient, experts warn the crisis may have longer-term effects. NIS gas stations remain stocked, but payments with foreign cards are already restricted an early sign of the financial isolation creeping in.

Why Russia Won’t Sell NIS: It’s Not About Money

Analysts underline that Gazprom and Gazpromneft under heavy losses since the Ukraine invasion are not holding onto NIS for profit.

The company brings minimal revenue to Russia.

The motivation is strategic and political: maintaining leverage over Serbian politics and the broader Balkan region.

This makes the situation even riskier for Serbia. If Moscow refuses to sell, nationalization becomes the only option and Vučić, attempting to distance himself from such a drastic decision, declared:

“We are not communists.”

Yet Washington has already made it clear: sanctions could be lifted if Serbia nationalizes NIS and demonstrates a clean break with Russian ownership. Belgrade now faces its own contradiction claiming it has no control over NIS while simultaneously insisting it can secure Serbia’s energy security.

“One of the Worst Strategic Choices Serbia Has Made”

Economists warn that the country is now trapped between two powers Russia and the United States because of a strategic decision made in 2008 that Serbia refused to reconsider even after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

As analyst Božo Drašković put it bluntly:

“We made a very bad strategic choice as a small country. The lesson is simple: vital sectors must never be left to foreign governments.”

Belgrade Keeps Repeating the Same Reassurances

Vučić continues telling the population not to panic promising that “buckets, canisters and other miracles will not happen again” even as the refinery in Pančevo risks shutdown if sanctions escalate and ownership is not resolved immediately.

Meanwhile, Moscow continues speaking as though Serbia is still firmly within its sphere of influence.

The Russian ambassador again insisted that Russia remains Serbia’s “reliable partner” and that Serbia’s energy security will stay intact “as it has so far” ignoring the fact that NIS is sanctioned precisely because of Russian control.

Ownership Games Continue Behind the Scenes

Just weeks before sanctions were enforced, a new Russian company quietly took over 11.3% of Gazprom’s shares in NIS an attempt that now appears like a last-second reshuffling designed to obscure Moscow’s role rather than reduce it.

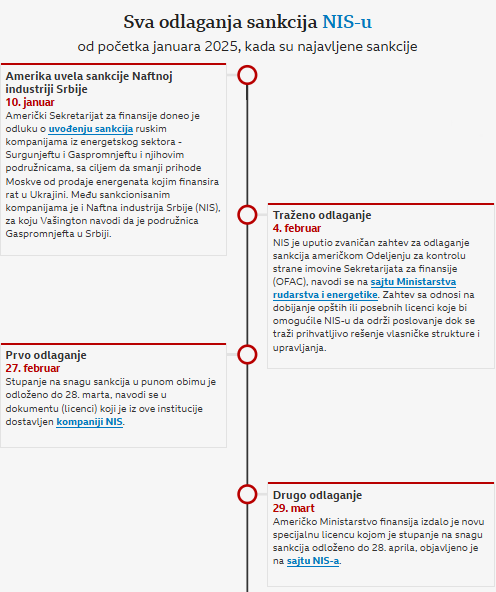

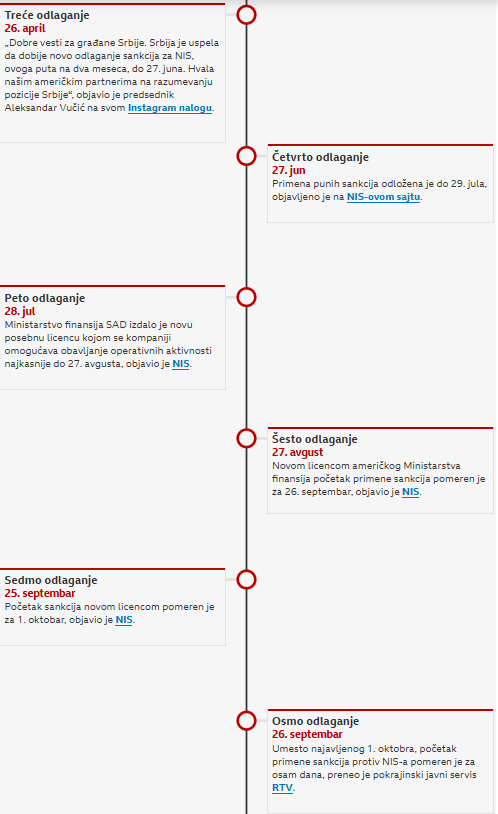

All sanctions delays:

In the end, Serbia’s crisis is not accidental.

It is the outcome of years of political hesitation, strategic dependence on Russia, and deliberate refusal to diversify energy ownership.

Now that sanctions have exposed the cost of those choices, Serbia is trying to present itself as a victim when it is, in fact, facing the consequences of its own decisions.