Belgrade, July 11, 2025 — Thirty years after the Srebrenica genocide, Serbia continues to grapple with its past, amid increasing international and domestic pressure to fully recognize one of the gravest atrocities committed on European soil since World War II.

While civil society groups and pro-European opposition parties in Serbia push for truth, justice, and dignity for the victims, the official stance of the Serbian government remains rooted in denial and revisionism. Despite international court rulings defining the 1995 massacre of over 8,000 Bosniak men and boys as genocide, the Serbian leadership persistently avoids using the term.

Researchers such as Branimir Gjurović from the Youth Initiative for Human Rights have highlighted that Serbia’s political and media space remains dominated by efforts to relativize the genocide. Convicted war criminals like Ratko Mladić and Radovan Karadžić continue to be glorified, with their images displayed in public spaces and their legacies defended in mainstream discourse.

“Since Aleksandar Vučić’s rise to power 15 years ago, denial and the celebration of war criminals have intensified,” said Gjurović. “Young generations are growing up with state-sponsored narratives that minimize atrocities and promote dangerous revisionism.”

President Vučić, in a statement marking the anniversary, referred to the events in Srebrenica as a “terrible crime” but refrained from labeling it as genocide. Meanwhile, Speaker of Parliament Ana Brnabić reiterated the government’s stance, outright denying the genocide classification, contradicting the findings of international tribunals.

Efforts by minority parliamentary groups — including the SDA Sandžak, Free Citizens Movement (PSG), and the Party for Democratic Action — aim to shift this narrative. A resolution submitted to the Serbian Parliament calls for formal recognition of the Srebrenica genocide, aligning with the 2024 United Nations resolution which designates July 11 as the International Day of Remembrance for the Srebrenica Genocide.

“We must end the propaganda and relativization,” said PSG MP Vladimir Pajić. “This resolution is not about blaming a people, but about aligning Serbia with historical truth and legal facts. Only through this can we build a democratic society and a shared future in the region.”

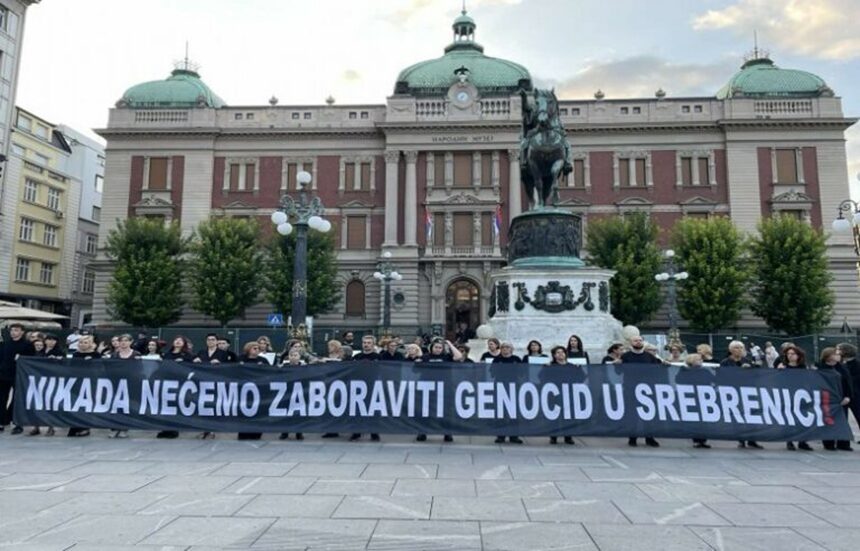

Civil society organizations such as Women in Black held memorial actions in Belgrade, demanding the removal of murals glorifying war criminals and calling on the government to officially declare July 11 as a national day of remembrance.

According to Gjurović, denial in Serbia extends beyond political rhetoric to cultural and academic institutions. “Recently, the Serbian Literary Cooperative publicly promoted a collection of Radovan Karadžić’s poetry, with praise from prominent intellectuals. In such an environment, genocide denial becomes normalized and socially accepted.”

Pro-European MPs and activists who visited Srebrenica on the anniversary expressed their commitment to justice and reconciliation, urging Serbia to confront its past honestly.

Without an official acknowledgment of the genocide, observers warn that Serbia risks undermining its democratic development and delaying its European integration. Civil society leaders argue that state-sponsored denial constitutes institutionalized revisionism, which jeopardizes regional stability and blocks genuine reconciliation.

As the region marks this solemn anniversary, the pressure mounts for Serbia to reckon with its past — not as a matter of political expediency, but as a moral and legal obligation toward peace and justice.