When Kosovo was engulfed in violence by the Serbian regime in 1998, hope for survival came from one address: the United States of America.

In May of that year, Kosovo’s political leader, Ibrahim Rugova, met with President Bill Clinton at the White House to report on the persecution faced by the Kosovar population.

“We asked the United States to act urgently to stop the violence and attacks in Kosovo. And the best solution is an independent Kosovo,” Rugova said after the meeting.

Clashes between Serbian forces and armed Kosovo Albanians were escalating daily, civilian casualties were deepening the crisis, and American diplomacy was intensifying.

James Rubin, then Assistant Secretary of State, recalled during testimony before the Special Chambers in The Hague that efforts to broker peace were dramatic, aimed at preventing a potential massacre of Kosovar Albanians through a peace conference in Rambouillet.

The conference ultimately failed: Serbia rejected the Western-proposed agreement, while Kosovo accepted it. Rubin noted that the U.S. fulfilled its promise to Kosovo’s political wing, led by Hashim Thaçi, by launching a military campaign when Serbia refused to sign.

On March 24, 1999, NATO aircraft began bombing, marking a pivotal chapter in Kosovo’s history.

“America has a duty to stand by our allies when they are trying to save innocent lives and preserve peace, freedom, and stability in Europe. That is what we are doing in Kosovo,” said Clinton that evening.

After 78 days of bombing, Serbian forces withdrew, and Kosovo was liberated. Thousands of U.S. troops entered as part of NATO peacekeeping missions, establishing the largest military base in the Balkans. Over the following years, the U.S. remained Kosovo’s key supporter, backing its path to independence.

On February 17, 2008, two days after Kosovo declared independence, President George W. Bush emphasized:

“The United States officially recognizes Kosovo as a sovereign and independent state. Kosovo commits to the highest standards of democracy, including freedom, tolerance, and justice for citizens of all ethnicities.”

Since 1998, the U.S. has invested over $2 billion in Kosovo, supporting everything from rule-of-law reforms to combating violent extremism and promoting Euro-Atlantic integration.

Today’s Challenges

The situation now is markedly different. Kosovo’s closest ally, the U.S., has suspended the Strategic Dialogue, citing actions by the interim government and rising domestic tensions. The Kosovo government rejected these criticisms.

“Our actions, legal and constitutional, have always aimed to eliminate sources of destabilization. The stability we enjoy today is a natural result of rule of law and public order,” wrote government spokesperson Përparim Kryeziu.

Interim Prime Minister Albin Kurti acknowledged “some differences” but maintained that relations with the U.S. remain intact.

Former U.S. Ambassador Jeffrey Hovenier explained that the suspension reflects frustrations accumulated over the past two years, including measures perceived as uncoordinated and detrimental to the Serbian community in Kosovo.

“The Strategic Dialogue allows for deeper cooperation: delegations travel to Washington, U.S. government departments engage directly, strengthening the bilateral relationship. Losing this opportunity is a significant setback,” Hovenier said.

Public reactions on social media were mixed, with some defending Kosovo’s interim government, while others criticized it for risking U.S. support.

Analysts’ Warnings

Regional experts caution that Kosovo cannot risk weakening U.S. support, as such a vacuum could be exploited by malicious actors like Russia.

Daniel Serwer, professor at Johns Hopkins University, emphasized the importance of maintaining U.S. military presence in Kosovo. Charles Kupchan from the Council on Foreign Relations added that it would be irresponsible to take actions that harm relations with a steadfast supporter.

A recent IRI poll showed that 77% of Kosovars see the U.S. as the country’s most important ally, underscoring public recognition of America’s role in Kosovo’s stability and independence.

Analysts stress that Kosovo must engage constructively with allies, not only the U.S. but also other countries such as Japan, South Korea, and Greece, to safeguard sovereignty and stability.

“Cooperation with allies does not undermine sovereignty; it is essential for maintaining it,” Serwer noted.

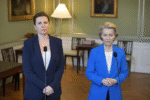

President Vjosa Osmani reaffirmed Kosovo’s commitment to strengthening ties with the U.S., emphasizing that the alliance benefits national security, regional stability, and Euro-Atlantic integration.

From Clinton and Albright to Bush and Biden, American support has been a cornerstone of Kosovo’s independence. Clinton himself visited Kosovo five months after liberation, urging forgiveness as a step toward sustainable peace:

“No one can force you to forgive what has been done to you. But you must try,” he said in November 1999.