The Serbian Parliament convened amid tension and spectacle, as opposition MPs paid tribute to the 16 victims of last year’s canopy collapse at Novi Sad railway station with 16 minutes of silence while outside, Diana Hrka, mother of one of the victims, staged a hunger strike blocked by police. One could almost admire the coordination: inside, endless debates; outside, silent protests.

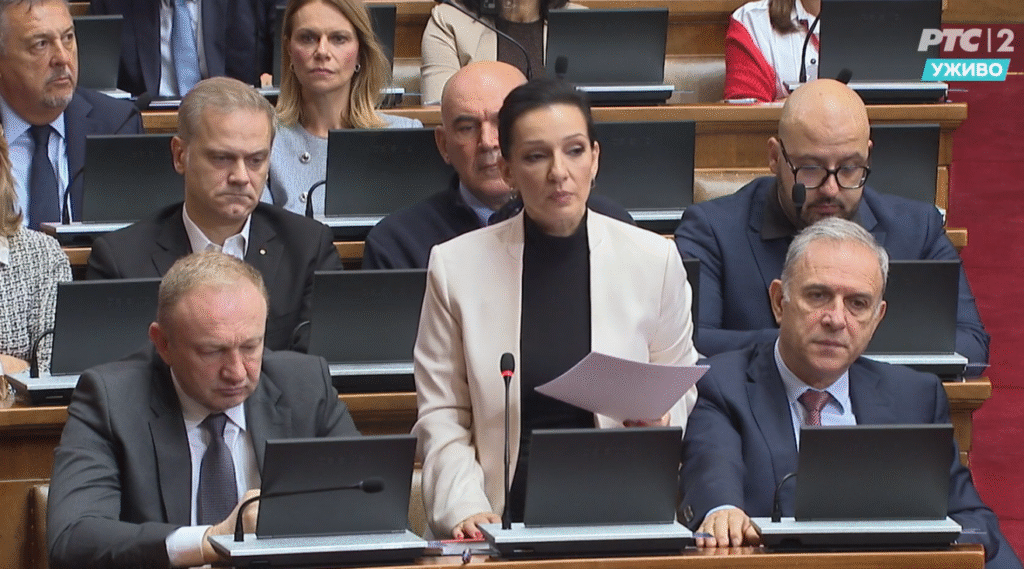

The Assembly’s agenda included amendments to the Law on the Unified Voter List and the controversial lex specialis for the General Staff building in Belgrade. MPs inside argued vigorously about voting rights, foreign interference, and corruption, while the outside world watched citizens being denied access to their own government—a fine example of participatory democracy.

Government MPs defended the legislation as “necessary” and “traditional,” claiming the General Staff building must be protected for future generations, presumably by handing it over to foreign investors. Opposition MPs, for their part, criticized the laws as tools for electoral manipulation and favoritism but mostly in passionate speeches that conveniently ended before any concrete action.

Miroslav Aleksić reminded the chamber that Aleksandar Vučić once received a state-owned apartment during NATO bombings while ordinary citizens lost theirs—proof, he said, of a long history of government favoritism. Opposition MPs called for accountability, better laws, and oversight. The irony? Many of the same opposition voices are accused of staging performative protests and wasting public time with endless filibusters.

Outside, Diana Hrka’s hunger strike drew support from students, citizens, and MPs, while pro-government agitators hurled insults and threats—because nothing says civil discourse like threats and intimidation. Meanwhile, some opposition MPs criticized the police for protecting the protesters, conveniently forgetting that political posturing often comes at the expense of real solutions.

The debates over voter lists and the General Staff building highlighted a fundamental truth about Serbian politics: everyone complains about corruption, nepotism, and broken institutions—but very few are willing to change anything themselves. In the end, both the government and opposition look remarkably alike: masters of rhetoric, arbiters of blame, and expert performers in the theater of politics.